The date - 3 November 1916. James Curran (my wife Sadie's great grandfather) was 60 years old when, on that dark and storm lashed Friday night he, with 96 other unfortunate souls, met a sudden and violent death in the raging seas of Carlingford Lough on a journey that he had not initially planned to take. Born and living in Rostrevor he was married to Alice Murdock from Burren. They had ten children, two of whom died young - Dora aged two by falling from a table and Sarah killed by a stone at age 16. It has been said that he accepted a ticket from an acquaintance who could not use it (and thereby saved his own life). He was going to Liverpool to work; I don't know where but it may well have been in the munitions factories, as England was then half way through The Great War in which more than 20 million people died. There is a family story that he was a seaman who was going to Liverpool to join his ship there. This may be so but it is not the occupation recorded on his 1901 and 1911 Census forms.

James was a strong swimmer and had often swum alone from Rostrevor to Carlingford. On the night before he sailed he had a dream. In his dream he was a seaman, crossing to join his boat at Liverpool, which he never reached. He dreamed he was frantically rowing a punt in heavy seas surrounded by pigs and cattle. His boat capsised and he swam ashore where he landed exhausted and streaming with blood. When he recounted this dream his friends and family urged him not to sail but he dismissed their fears as groundless.

An hour before he sailed he discovered he needed a button sewn on his shirt. This buttom was significant as we shall see.

The Ships

The SS Connemara was a sturdy vessel of 1106 gross tons. She was a twin screw steamer, 272 feet long, 35 broad and 14 deep. She had been build by Denny Brothers of Dunbarton in 1897 and put to work by her owners, the London and North-Western Railway Company, on the lucrative Holyhead & Greenore service - "The Direct & Most Comfortable Route Between London & Belfast & The North of Ireland", which had been inaugurated in 1874. Greenore is on the Carlingford peninsula of County Louth, about four sea miles over the water from Rostrevor, in County Down. The Connemara's Master, 50 year old Captain GH Doeg, and his crew of 30, all from Holyhead in Wales, were experienced seamen and well used to rough weather.

The "Retriever", the other ship involved in the tragedy, was a 483 -ton collier owned by the Clanrye Shipping Company, built by Ailsa Shipbuilding Company in 1899. She was a steel screw, three masted steamer, 168 ft long, 25 broad and 10 deep. She had a crew of nine. The Captain was Patrick O'Neill from Kilkeel. The Second Mate was his son Joseph and one of the seamen, Joseph Donnan, was his son-in-law. The sole survivor of the tragedy, James Boyle, from Summerhill in Warrenpoint, was a fireman on the Retriever. The other seamen were from Newry.

Both the Connemara and the Retriever had been previously in collision with other ships. The Connemara sunk the Liverpool vessel Marquis of Bute on 20 March 1910. On 31 August 1912 the Retriever sunk the Spanish ship, the Lista, at Garston dock. This accident was due to the sudden death on the bridge of the Captain of the Retriever as he was taking his ship out of the dock.

The Passengers

The 51 passesngers were a mixed group. Some were soldiers returning from leave, some recovered from wounds suffered in Flanders. There were people from Sligo, from Longford, from Ballybay in Monaghan, from Cavan, from Crossmaglen and Cullyhanna in South Armagh, from Dundalk in County Louth, from Ballycastle on the north coast of Co Antrim, and further afield. Many were on the first steps of emigration to America, in search of a better life. Others were visiting relations in great Britain. There were drovers who were to accompany the large number of cattle and sheep that were making the crossing and many were young girls making for the munitions factories.

Miss Williams, Stewardess on the Connemara, was making her final trip before leaving to get married. Patrick Conlon, a Dundalk railwayman, was travelling to Wigan with two female cousins - Mrs Lily Fillington and Mrs M. Clarinbroke - and Mrs Fillington's two children. A woman and her three children were going to England to meet her soldier husband home from the front.

Each death was a tragedy for the people concerned and for their families and communities. How each one arrived at their fate was a personal journey. Some potential passengers were saved by fortuitous circumtances, others who met their fate by ways that were also fortuitous. Some of these stories follow.

Mrs Small, of Birkenhead, whose husband, a mining engineer, had died on his way home from West Africa in September, had arranged to return home with her daughter from Greenore. However, on Thursday night she dreamed that she had sailed in the Connemara and that she saw the vessel founder. She regarded the dream as a warning and refused to sail, thus saving both their lives.

Mr P.J. Kearney, and his sister, Miss Catherine Kearney, children of the Principal of Drumilly National School, Whitecross were waiting at the Edward St Station in Newry. Mr Kearney had recently completed his training in Waterford for national school teaching, Miss Kearney assisted her father in the school. They were going to meet a married sister who was coming from America. While waiting for the train to Greenore they were told by Sergeant Fitzpatrick, who was always on duty at the station, that the Greenore boat on which they meant to embark might not sail as the night was so rough. After some hesitation Mr Kearney tossed a penny on the Waiting Room table and on an the strength of the result decided to make the journey.

Mary McArdle, from Crossmaglen, Co Armagh, who travelled from Dundalk to Greenore, was bound for New York. She had intended to travel to Liverpool by the Dundalk and Newry Steam Packet Company's boat on Wednesday, but missed the sailing. She waited over in town until the Friday, and caught the evening train.

John Loy, of Leish was told that his son, who had been wounded at the front, was in hospital in England and was making ready to go on the Connemara, but his wife, seeing how wild was the night, succeeded in keeping him at home, thereby probably saving his life.

Henry George Tumelty, of High Street in Newry, a fireman on the Retriever, missed the sailing at Newry on its last trip to Garston. He cycled three miles along the canal and jumped aboard the ship as it was passing out of the locks at Fathom.

The Collision

The Retriever had left Garston for Newry, with a cargo of coal, at 4 am on Friday morning but, according to James Boyle, the gale force winds and mountainous seas had slowed her progress and shifted her cargo, although he maintained that this did not unduly affect her handling.

The Connemara left her berth at Greenore at shortly after 8 o'clock bound for Holyhead on her regular run. A fierce gale was raging ("The wildest night he had experienced in 70 years" according to one old farmer in the area). The hurricane force wind was from WSW against a strong ebb tide of some eight knots. About two and a half miles from Greenore she passed the Halbowline lighthouse (marking the Carlingford bar) and entered the comparatively narrow channel, or "cut", leading to the open sea. The "cut" is about 300 yards wide and, in the prevailing conditions of wind and wave, afforded no great leeway for vessels to pass each other. Conditions in the channel were atrocious. The combination of wind and tide had churned the sea into a fearful cauldron at the bar mouth, making navigation difficult.

About half a mile beyond the bar the Connemara met the Retriever inbound from Garston. Both vessels were showing their lights and these is no reason to suppose the least lack of care from either of their masters. The watch at the Haulbowline lighthouse, seeing the ships too close for comfort, fired off rockets in warning. Almost immediately the crash happened. The Retriever, battling against the wind and tide, and with an unstable cargo, was caught by a huge gust and swung into the side of the Connemara, penetrating the hull to the funnel. For a moment the ships locked together, then the Retriever, having apparently reversed engines just before the impact, swung wide and the Connemara, terribly ripped from the bow on the port side to amidships, sank within minutes, the boilers exploding when the sea entered the engine room. The Retriever, with her bows stove in, took about twenty minutes to perish. Its boilers also blew up on contact with the sea and she sank about 200 yards from the Connemara. In all, 97 people died. Twenty one year old James Boyle, who was the only non-swimmer among the crew of the Retriever, and who had been below deck when the collision happened, was lucky to survive, clinging precariously to an upturned boat and avoiding being dashed against the rocks. William Hanna, the son of a farmer at Cranfield, finally pulled him ashore after about half an hour in the raging seas.

Alerted by the rockets, people from Cranfield to Kilkeel flocked to the beaches but such were the condition of the wind and the sea that there was nothing anyone could do but keep vigil in the vain hope that they might be able to help some struggling survivors from the surf. Had it not been for that vigil, James Boyle might have perished within reach of safety.

An odd feature of the disaster was that news of it did not reach Greenore (less than three miles away) until 9:30 the following morning as the lighthouse keeper signalled to the Co Down coast.The Survivor's Story

Boyle was taken to Hanna's house and cared for until his family arrived from Warrenpoint to take him home. His story, which he refused to discuss all his life until interviewed as an elderly man for television, was harrowing in the extreme. As he recalled it, the Retriever was steaming towards the leading lights that mark the entrance to the channel. Half a mile away, between the lighthouse and Greenore, the Connemara could be seen ploughing steadily along. Both ships showed lights and were on the proper course.

Boyle was taken to Hanna's house and cared for until his family arrived from Warrenpoint to take him home. His story, which he refused to discuss all his life until interviewed as an elderly man for television, was harrowing in the extreme. As he recalled it, the Retriever was steaming towards the leading lights that mark the entrance to the channel. Half a mile away, between the lighthouse and Greenore, the Connemara could be seen ploughing steadily along. Both ships showed lights and were on the proper course.

"Just as I thought the two ships were about to pass, I went down into the cabin to attend to the fire. The Retriever's whistle sounded three times and, suspecting that something out of the ordinary had happened, I rushed up the stairway. Before I reached the deck there was a collision, and our ship shivered from stem to stern.

Contrary to what one might suspect, there was no panic or confusion on the Retriever. Captain O'Neill, who had been on the bridge all afternoon, gave the order, in a clear firm voice, for the crew to take to the boats. Boyle, William Clugson, and Joe Donnan immediately went to get one of the two available boats ready for launching. They were joined by Joe O'Neill. Joe Donnan went below for lifebelts and advised them to remove their seaboots. Boyle continued,

"That was the last I saw of him, although I heard his voice a few minutes later crying 'Cut her away, cut her away.' The Retriever took a heavy lift to starboard, swinging the boat well out from the side. I was holding on to a rope ready to jump into her. It was then that I heard Donnan shout, and I cut her away, springing in at the same time. I don't know what became of the others. I drifted away clear of the steamer, which had parted from the Connemara after the collision. The mail boat sank in about seven or eight minutes. I heard no shouts from her, and cannot tell you what happened aboard her, but just before she went under she was very low in the water, and she seemed to be on fire."

The Retriever listed more and more and eventually went to the bottom but young Boyle's troubles had only begun. His boat, tossed about for half an hour or so, was capsized by a mountainous wave. Boyle clung to the keel and drifted towards the shore. Another huge wave swept him and the boat out to sea again but righted the boat at the same time and he was able to climb aboard once more. This happened a second time. Eventually, on reaching the surf the boat capsised for the third time and exhaused to the point of helplessness, Boyle thought that his end had come. However, when he felt the sand under his feet he started to crawl through the surf where William Hanna, with Tom Crutchley, found him and carried him to Hanna's house, half a mile from the shore, where he was cared for until his family arrived to take him home to Warrenpoint.

The Aftermath

By morning, the shoreline was littered with wreckage, the carcases of animals and the bodies of the passengers and crew of the ships. On the first day 58 bodies were found, many badly burned and mutilated. By Sunday afternoon a number had been identified. Among them was James Curran. He was found on Cranfield beach and was identified by the button (which was a different colour to the other buttons) which had been sewn on his shirt just before he left. His body was taken back to Rostrevor where he was buried in Kilbroney Graveyard on Tuesday 7 November.

The strange twist to this tale is that his dream recreated the actual experience of the sole survivor.

For many days bodies of people and animals were washed up along the coastline from Cranfield to Kilkeel. Some took weeks to arrive on land. The scenes of grief and dispair as people identified their loved ones were harrowing in the extreme. The bodies of the dead passengers and crew were temporarily stored in barns and people's houses, those identified being taken home by their families. Some were never identified and were buried in Kilkeel. A number of appeals were made for financial assistance to the bereaved families and Trust Funds established.

The inquest was held on 6 November in Kilkeel, the Coroner and members of the Jury journeying to the scene of the tragedy to view the wreckage and the bodies that had been collected. James Boyle gave his evidence, on the lines outlined above, breaking down several times as he recounted the events of that terrible night, only two days before. The verdict was death by drowning caused by the collision of the ships.

Until the sinking of the Princess Victoria in 1953, when 128 died, it was the worst tragedy to hit the County Down Coast.

James Boyle lived on in Warrenpoint for another 50 years - he died on 19 April 1967.

In Dublin, the tragedy inspired a sixteen year old schoolboy, C.A. McWilliam, to write a poem - The Collision of the "Connemara" and "Retriever"

Listen to Lovely Alice: The Connemara and Retriever Song by Pauline McQuaid Shields, great-granddaughter of James and Alice Curran.

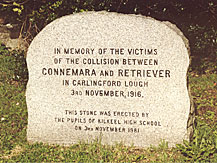

On 3 November 1981 the pupils of Kilkeel High School erected this stone in Kilkeel Graveyard in memory of the victims of the tragedy.

Footnote: It was reported that the ghost ship "Lord Blaney" had been seen some days before the tragedy.

See also: www.irishships.com

Back to James Curran